Real Estate 101

Tom Hardy • May 2, 2020

Understanding the Capital Stack

Students in the Real Estate Copowerment Class Photo Courtesy of Neighborhood Allies

One of the most interesting things I get to do is teach the basics of real estate finance to folks that have little or no background in the subject but are motivated by a strong desire to learn. Neighborhood Allies

and Omicelo Cares

launched the Real Estate Copowerment Series in 2017. Some participate because they want to learn to invest on their own, and others attend because of a desire to learn about the forces reshaping the neighborhoods they live in. When we start, I explain that the math is relatively simple, but the language and terms are often unfamiliar. So let’s start with the basics.

Understanding Leverage

The first concept in real estate development is the use of leverage, or more simply stated the use of borrowed money. Rental real estate generates income that can be used to cover loan payments. Banks and other financial institutions make these loans based in part on a rental property’s expected net operating income (NOI). Net operating income is just the collected rents less a property’s operating expenses (insurance, utilities, maintenance, etc). Banks play a much greater role in financing real estate than they do in financing other types of investments. Here’s a simple example.

If I buy the four-unit property, I have leveraged the $100,000 into ownership of $400,000 in real estate assets.

Banks are generally willing to lend more for each dollar of value for a real estate asset than for other types of assets or operating businesses. This is because real estate tends to produce more predictable and stable cash flows when compared to other types of investments and operating businesses. Real estate is not insulated from market downturns, and the most highly leveraged properties are particularly susceptible to these downturns.

Components to the Capital Stack

The capital stack refers to the different sources of funds used to finance a real estate project. Real estate is costly to purchase and maintain. Developers and real estate investors raise money from multiple sources. The largest component of the capital stack is typically a bank loan. Banks go through an extensive process to determine if and how much they will lend to a real estate project. One underlying principal is that they lend only a fraction of the appraised value of the project—typically a maximum of 65% - 75% of that appraised value. That is known as the loan to value ratio.

With my four-unit apartment acquisition, I am going to have to come up with the other 25% of the project’s value with my cash contribution known as equity. My bank is only willing to lend to me if I have some of my own money at-risk in this project. The bank wants to be sure I have some “skin in the game” and that I have a financial interest in the success of the project. For a market rate development project, the typical capital stack may consist of only two sources – bank debt and owner’s equity.

The Difference Between Appraised Value and Cost

A fundamental real estate concept, particularly for community development, is understanding that a real estate project’s appraised value can be different than its cost. This is best illustrated by an example. Let’s say I am building a 25-unit apartment building in the area of town where rents are high. Once completed, I project I will collect $400,000 in annual net operating income (collected rents – operating expenses). If I try to build that same building in a part of town that is less developed, where rents are lower, I might generate only 75% of that amount in net operating income. But it would cost me roughly the same amount to build that building. My land cost is lower in the less developed neighborhood—but the bulk of my costs are construction costs which are roughly the same regardless of which neighborhood I am building in.

So, if the cost of building two of the same apartment buildings in different neighborhoods is roughly the same, what are the market values of these two buildings? Determining market value in real estate could be the subject of another post or entire class, but for now we are going to simplify. Let’s take the net operating income of each of the buildings divided by the market’s expected rate of return in each of these neighborhoods (this rate of return is called a capitalization rate or cap rate for short). This calculation will give us an estimate of fair market value. See the example below.

What is the “Financial Gap”?

The financial gap is the difference between my project’s cost and the amount of bank debt and equity I can raise. As we went over earlier, the bank is only willing to lend a fraction of the project’s appraised value. As developer, I will put in some money as equity but only to the extent I can earn a reasonable return on that money. The formula for the financial gap is simply: Financial Gap = Project Cost – Debt – Equity. Using the example above the financial gap of the apartment building in the weak market neighborhood is calculated as $6M (my project’s cost) - $4M (my project’s estimated as completed market value. This results in a financial gap of $2M.

For a purely private sector potential project, we would stop at this point and say the project is not viable or that it doesn’t “pencil out”. With a community development lens, if this project fulfills an important public policy objective (i.e. affordable housing, community facility, etc.) we may wish to work to fill the financial gap using financial resources from our community development toolkit.

Addressing the Financial Gap

Neighborhoods where real estate prices are increasing rapidly make frequent headlines. A few miles from where I write this is Pittsburgh’s Lawrenceville neighborhood which has seen median prices nearly triple in less than twenty years. While these “hot” neighborhoods get plenty of press, this obscures the fact that there are many neighborhoods in both big cities and small cities that have seen prices stagnate or even decline. These are neighborhoods with high rates of vacancy and blight and have seen little or no new development in decades. In order to work with local neighborhood stakeholders to facilitate real estate development in these neighborhoods we need to work together to bridge the gap between what the private sector provides (debt & owner equity) and the total amount of financing needed to complete a project.

Sources of Gap Financing

Gap financing typically comes from three sources: public sector, tax credit equity, and the non-profit sector through Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI’s) and philanthropy. Public sector funds vary based on the type of project, but community development block grants (CDBG) are are often directed to development in low-income neighborhoods. State governments typically have competitive gap financing dollars that they will invest in project. One example in Pennsylvania are housing trust fund dollars that are administered through the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency (PHFA). Local governments sometimes will invest capital budget dollars as gap funds for projects. These gap financing investments typically take the form of grants or deferred loans.

There are several prominent tax credit programs that allow private investors to take credits on their federal income tax liability for investing in qualified projects. The most prominent of these tax credit programs include the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), and Historic Tax Credit (HTC). Transaction costs with these credits are significant, so most projects that utilize them have total project costs of more than $5M. Some states have enacted state tax credit programs. For example, Pennsylvania has a historic tax credit program that offers credit against state tax liabilities and as of this writing is considering a low-income housing tax credit program.

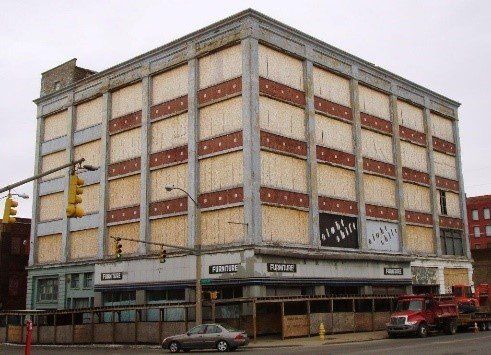

Before and after pictures of the Mercantile Building in Erie that we were involved with. Project utilized a number of gap financing tools.

Gap financing has helped bring a bakery and coffee shop to 2nd Avenue in Pittsburgh's Hazelwood neighborhood.

Only projects with complete capital stacks can move forward. This is an all or nothing proposition. Having 90% of a project’s capital stack does not get you 90% of a project. In this scenario, if we can assemble gap financing covering 10% of the project’s cost, we can unlock the other 90% of the project’s financing. Gap financing leverages other private dollars. Used strategically, gap financing is a critical development tool that neighborhoods can use to facilitate development.